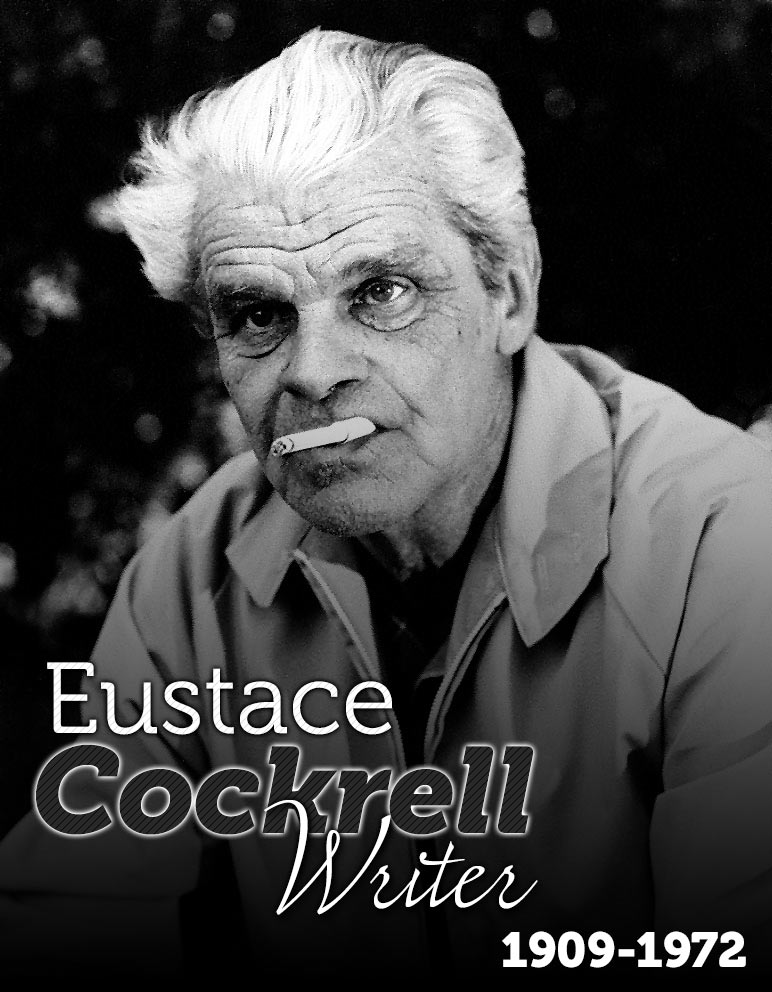

THE MANY TRANSITIONS OF HOLLYWOOD

ICON, EUSTACE COCKRELL*

Eustace Cockrell was born in the small Missouri town of Warrensburg. His was a prominent family. Cockrell’s grandfather, Francis Marion Cockrell, was an attorney who became a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army and later served as U.S. Senator for six terms (1875-1905). Cockrell’s father, Ewing Cockrell, was a judge who moved to New York and was later nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize related to his work in developing the Federation of Justice, an organization seeking reforms within the American justice system.

As a result, Cockrell grew up shaped by a culture that still remembered nearby Civil War battles (Battle of Lone Jack); the nighttime raids of William Quantrill, the pro-Confederate guerrilla warfare leader; the exploits of Jessie James; and the politics of small-town life. (His grandfather’s law partner, Thomas T. Crittenden, went on to become governor of Missouri and was famous for rounding up the James Gang and restoring order to a lawless frontier.)

In addition to these dramatic influences, Eustace Cockrell followed in the footsteps of another famous Missouri writer, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) with reminders of Clemens to be found in Cockrell’s use of humor and in the use of dialect to quickly develop his characters.

*More detailed biographical information about Eustace Cockrell can be found in the Introduction to any of the volumes of the author’s “Collected Works.” (See PURCHASE BOOKS)

Early Writing Career – Pulp Fiction Magazines

Cockrell’s first published story was a boxing story, co-authored with his older brother, Francis M. Cockrell. It appeared in Blue Book Magazine in 1932. Eustace Cockrell was 22 years old at the time.

Cockrell continued to write throughout the 1930s primarily for pulp fiction magazines like Blue Book, Argosy and Adventure but also for other general interest publications including Holland’s: the Magazine of the South and Liberty. While his tales covered a broad spectrum of fiction categories – detective, adventure, romance and even science fiction – his early stories often featured sports themes with professional boxing and college football among his favorite settings.

Cockrell is at his best, however, when contributing tales of political intrigue, a subject based on the first-hand experiences of his grandfather (who lost the governor’s race in Missouri before becoming Missouri’s U.S. senator) and his father (who lost a race for the Missouri House of Representatives before becoming a Circuit Court Judge). “Bill of Engagement” (Holland’s Magazine, February 2, 1936), a story of corporate lobbying influences, though written 87 years ago, is not far removed from present day realities. (This story can be found in The Lost Stories of Eustace Cockrell, Vol. V of the author’s Collected Works. See BOOKS.)

Writing during the Great Depression (1929 – 1939), Cockrell’s stories provide excitement, adventure and escape for those suffering from the economic hardships of the Depression. His tales during this period featured orphans, ex-cons and down-and-outers able to overcome their personal limitations to find, if not wealth, at least self-respect.

Writing for the “Slicks”

In the late 1930s, Eustace Cockrell, after spending time in New York, joined his brother Frank in Los Angeles. Here he met Betty Barnett, another writer, while she was working as an extra on a Hollywood movie set. The two were married in 1939 and, over the next 12 years, had four children – Leacy, Geoffrey, Frederick and Elizabeth.

It was during this period that Cockrell made a transition from writing primarily for pulp fiction publications to writing for “slicks” like Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, The American Magazine, Cosmopolitan and Esquire. Part of this change was due to the decreasing popularity of pulp magazines and the growth of general interest publications able to attract more sophisticated readers with their full-color, contemporary look. Cockrell was represented by Paul R. Reynolds, one of the top literary agents of the period.

His writing continued to focus on sports themes but more often featured golf, tennis and horse racing rather than boxing or football. Too, as the U.S. became involved in WWII, Cockrell added soldiers in his stories with a special focus on the difficulties they faced in returning home from battle.

By the end of the decade, Cockrell began to express greater awareness of social issue and

a rebellion against restrictive attitudes in his writings, especially those limiting the role of women and minorities. An example is “Beauty and the Drop Kick,” Cockrell’s 1948 story in Collier’s featuring the first woman to play football for a major college team.

Still, it was one of Cockrell’s boxing stories that brought him to the attention of the Hollywood movie industry.

Initial Hollywood Involvement

In 1940 Eustace Cockrell introduced a boxing character who went on to become the middle- weight world champion. Refugee Smith, one of the initial fictional Black heroes to be featured in a major American publication, first appeared in “The Lord in His Corner” (Collier’s (April 13, 1940). The fourth episode in the Refugee Smith series, “Complements of R. Smith” (Collier’s, December 28, 1940), caught the attention of movie producer Allen Freed who was just beginning development of an MGM production, Cabin in the Sky, based on the hit Broadway musical. Cockrell was hired by Freed to assist with writing dialect for the production, one of the first movies featuring an all-Black cast (Lena Horne, Ethel Waters and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson).

This contact with MGM turned out to be a turning point in Cockrell’s writing career with MGM also purchasing the rights to the Refugee Smith stories and eventually releasing a film based on this collection. Tennessee Champ, directed by Fred M. Wilcox and featuring Shelley Winters, Keenan Wynn, Dewey Martin and Charles Bronson, appeared in 1954.

Another of Cockrell’s published stories, “Rocky’s Rose” (The American Magazine, October 1949), was purchased by MGM and released in 1953 as Fast Company. The movie, about double dealings in the horse racing industry, starred Howard Keel, Polly Bergen and Nina Foch.

Neither Fast Company nor Tennessee Champ were box office hits and except for a stint working under contract with Warner Bros. beginning in 1946, Cockrell’s movie involvement was limited. He was, however, later nominated for an academy award (1953) as part of a team that produced Operation Blue Jay, a documentary covering the construction of the secret Thule Air Base in Greenland.

Articles and Editing

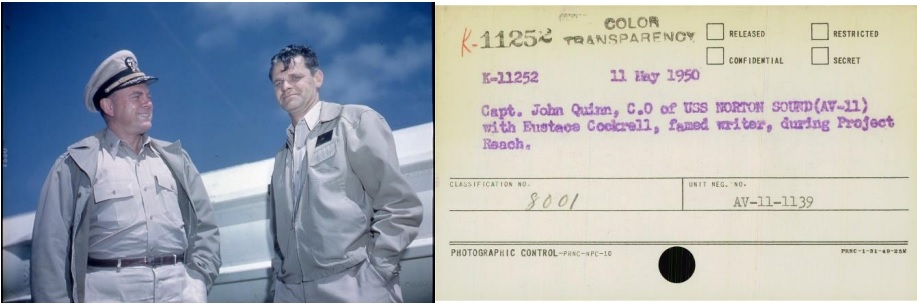

Capt. John Quinn (left) with “famed writer” Eustace Cockell aboard the USS Norton Sound (Photo courtesy of the National Archives).

Partly because of the growing popularity of movies, the general interest magazines also began to decline as outlets for fictional short stories. In response, Cockrell began to add non-fictional writing to his portfolio. In 1945, he ghost wrote Stardust Road, an autobiography of song writer Hoagy Carmichael. Collier’s contracted with him in 1949 to travel throughout the U.S. to interview “millionaires” although there is no indication that this series was ever published.

Cockrell began writing for Armed Forces Radio in the late 1940s and received fame for his coverage of Project Reach, the highly secretive testing of a Viking rocket launched from the USS Norton Sound in 1950. One of his stories written aboard the ship, “Obituary of Torridtail,” is included in The Lost Stories of Eustace Cockrell. (See PURCHASE BOOKS)

From 1951 to 1955, Cockrell was managing editor of Fortnight, a California news magazine edited by close friend and fellow writer, Richard Matheson (I Am Legend and The Shrinking Man).

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the author had made a series of transitions, not so much in general themes, but in the outlets available for his writing. These transitions reflect both changing times and his increasing writing skills. Beginning with the pulp fiction magazines, moving to the general interest publications, then to the MGM movies followed by the editing and writing for non-fictional publications, Cockrell was well-prepared for the next transition – the advent of television. It was this final transition that brought him recognition as a pioneer writer during television’s “Golden Age.”

“Golden Age” of Television

Moving from writing for magazines to writing stories and teleplays for television is a complex undertaking requiring a combination of writing and technical skills often outside the range of one person. Cockrell’s initial involvement in television began not with the writing of teleplays but with having his stories adapted by other writers. “The Power Devil,” for example, co-authored with Herbert Dalmas, first appeared in The American Magazine (December 1949). In 1950, William Kendall Clark adapted the story into a teleplay for Philco Television Playhouse (November 5, 1950).

Other Cockrell stories became teleplays for television shows including episodes of The Loretta Young Show (March 19, 1954) and The Damon Runyon Theatre (January 21, 1956).

Cockrell’s first published short story was co-authored with his older brother, Francis M. Cockrell, in 1932 (Blue Book). In 1956, the Cockrell’s again teamed up to contribute teleplays for two episodes in the first year of Alfred Hitchcock Presents (“A Bullet for Baldwin,” January 1, 1956, and “You Got to Have Luck,” January 15, 1956).

The Cockrell Brothers also contributed two episodes for The Web (“No Escape,” July 28, 1957, and “Dead Silence,” September 22, 1957) and two episodes for Man Without a Gun (“Silent Town,” January 15, 1958, and “Man Missing,” June 12, 1958). A final collaboration was an episode for The Walter Winchell File (“David and Goliath,” January 31, 1959).

Eustace Cockrell contributed stories and teleplays for a variety of other shows including Target, Cheyenne, Jefferson Drum, This Man Dawson, Two Faces West and Naked City.

He was also under contract with Warner Bros. to help edit some of this studio’s western television programs – Sugarfoot, Maverick and Have Gun Will Travel.

While Cockrell had matured so that he could successfully write teleplays for drama programs with themes of suspense (Alfred Hitchcock Presents) or crime investigations (This Man Dawson), he was most at home writing for the television westerns.

Here, the author could draw upon his early experiences in the midwestern town of Warrensburg, Mo, combining the small-town setting with his overall theme of lifting the lowly and humbling the arrogant – a good guy/bad guy combination that was at the heart of the successful early western television shows.

In “Drought,” (Two Faces West, January 9, 1961) for example, a show that features twin brothers, one who carries a gun and one who publishes a newspaper, Cockrell presents a conman in the form of a “rainmaker.” Gliyyas Hatfield ends up bilking the desperate farmers of their life savings only to have second thoughts and return their money. At this point, thunder is heard and the initial rain drops begin to fall. There is dancing in the street.

Corny perhaps, but hopeful, and Cockrell at his purest.

(See MOVIES/TELEVISION SCREENPLAYS for a complete list of Eustace Cockell’s television contributions.)

The Legacy of Eustace Cockrell

For 30 years, the stories of Eustace Cockrell thrilled American audiences. As a person, Cockrell had a strong sense of personal integrity and an unyielding belief in the goodness of people and their ability, regardless of circumstances, to persevere and overcome mistakes made early in life. (Eustace Cockrell was a life-long member of AA.) There are few evil characters in Cockrell’s stories, at least not by the time the story ends. Everyone gets a second chance.

This optimism remained throughout his career even as he faced the challenge of writing for ever-changing audiences and the growing influence of Hollywood’s movie and television industry. As one friend commented about Cockrell, “He was never corrupted by the greed, the self-indulgence and the inflated egos that ruled Hollywood.”

Whatever the challenge, Cockrell rose to the occasion. Like his characters, he persevered through the ups and downs and the many transitions required to become an exemplary and much respected mid-century American writer.

Photo: Eustace and Betty Cockrell with their children – Leacy, Frederick, Elizabeth and Geoffrey (circa 1953).